Weaponizing the Groovy script console: Bindshells & base64 tool transfers

__OVERVIEW

Have you ever been in an engagement or CTF where you finally find a Groovy script console… and then discover outbound connections are blocked? or you can’t get tools to the target using built in upload methods?

Over the next few minutes I’ll show a practical, repeatable approach for turning a Groovy console into a persistent, multithreaded JSP bind shell that lives in the webroot and how to transfer binary tools via base64 encoding (small and large size). this guide serves as a proof of concept, the shell in here is not secure enough for opsec, but it’s a starting point for you to build upon.

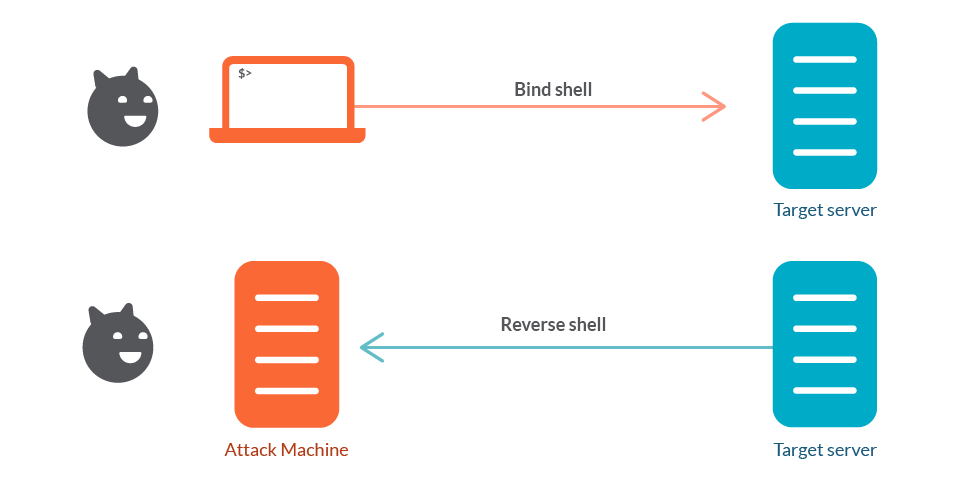

Quick Referesher on bind shells:

The top side shows a bind shell: the victim host runs a listener (a shell bound to a TCP port) and the attacker connects into that listener to gain interactive access. The bottom side shows a reverse shell: the attacker runs the listener and the victim initiates an outbound connection back to the attacker, delivering a shell to the attacker’s listener.

Reverse shells are the go-to for many red-teamers because they slip out through egress and work around NAT. But when outgoing traffic is tightly restricted (egress-blocked/proxied), you need a plan B. that’s when I focus on bind shells. In short: a bind shell makes the target listen and waits for an inbound connection. It trades the egress dependency of a reverse shell for a requirement that you can reach the host inbound (or via a pivot you control). That trade can be exactly what you need when defenders have locked down outbound channels.

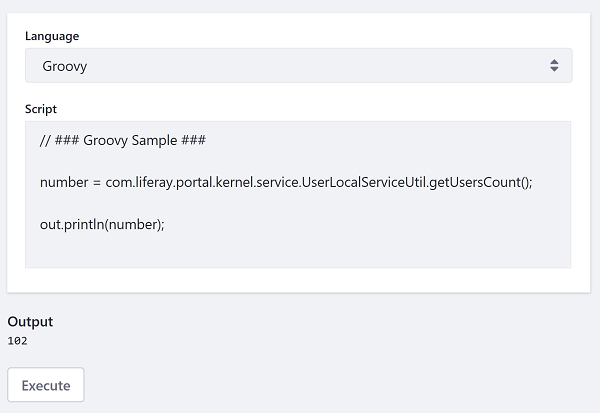

Groovy Console to Bind Shell:

When your RCE is limited to a Groovy-style script console (Jenkins, Liferay, etc.) and the target cannot reach back to you, the console itself becomes your primary file-system and transfer channel. This post focuses on turning that console access into a stable way to read/write files,and drop tools. Treat the console like a tiny development environment on the target: you can list folders, create files, and write binary blobs (via base64) into disk locations the web server will execute or serve.

Deploying the bind shell:

high level steps:

- Discover writable paths (where you can save files that persist and potentially get executed or served).

- Transfer binary tools via base64/text encoding and write them as raw bytes on disk.

- Verify permissions & execute (browse to webshell to load your bind shell).

- Clean up and document detection artifacts.

Simple OS commands POC:

POC script for running simple commands such as pwd, ls, dir, cd and trying to identify where the web root might be located:

Linux: pwd, ls -la, id, whoami, env |

def cmd="YOURCOMMAND-dir" |

1) Finding stable, writable locations

From the console, run simple listing commands to map the filesystem and locate likely writable paths.

Typical candidate locations:

- Application webroot (e.g.,

<TOMCAT_HOME>/webapps/ROOT) — files here can often be triggered by HTTP requests.

2) bindshell > a better alternative to webshells

This is where my bind shell comes into play: https://raw.githubusercontent.com/vipa0z/jenkins-liferay--stable-bind-shell/refs/heads/main/persistent_bind_shell.groovy

Use this link to access the code. Paste it into your Groovy console after updating the output path to match your Tomcat webroot.

Hit save, then to enable the listener, browse to your webshell at: http://site/threaded.jsp

Connect to the bind shell via netcat:

example 1: |

Tips:

- Prefer non-volatile locations that survive process reloads if you need longer-lived access (webroot > in-memory-only artefacts).

- Check file ownership and mode (ls -la) to avoid placing files you can’t later run or overwrite.

- If multiple app instances exist (e.g., separate webapps), target the one whose webroot is public-facing.

2) Tool transfers using the groovy script console:

if for some reason you are not able to abuse built in upload functionality to have tools into the file system, you can use the groovy script console to read and covert tools that are base64 encoded with this console script:

note: this will not work if your base64 is more than 6000 in length, you can use the chunking method below to transfer large base64 strings.

for smaller sized tools (eg: netcat, potato exploits..etc):

base64 encode the tool and copy to clipboard:

base64 --wrap=0 tool.exe | xclip -selection clipboard -i |

paste the base64 into the console

import java.util.Base64 |

For Larger Binaries

I put together a script that chunks your tools into smaller base64 files (6000 chars per chunk by default), so you can paste them into the console and reassemble them with Groovy.

Script: https://raw.githubusercontent.com/vipa0z/Groovy-bind-shell/refs/heads/main/tool_chunker.py

run:

python3 tool_chunker.py yourtool.exe -o <output_dir> -s 6000 |

Options:

-s: chunk size (default 6000)-o: output directory-h: help

The script outputs numbered chunks (part1, part2, etc.) and shows you what to do next.

Example:

python3 tool_chunker.py -s 6000 XecretsEz -o xcretsez |

Steps:

Run the script as shown above

Paste into the script console

Copy the Groovy reassembly code from the script output and paste it below your base64 blobs

Double-check the write path is correct

Save and run

Verify It Worked:

After dropping the file, sanity check it:

Compare file size

Hash it (MD5/SHA256) and compare with the original

That’s it! Quick recap: find writable paths, use base64 (chunked if needed), verify integrity, and clean up your artifacts when done.